Why you should improve proficiency at air polishing

What has changed little over the past 50 years and is the most performed yet overvalued service provided in dental practices? If you guessed rubber cup polishing, you’d be correct.

Overvalued? Sure—from a health perspective, polishing is more or less a cosmetic procedure. Then why do most patients still get their teeth polished with prophy cups and paste? It’s certainly not because it’s the most thorough way to remove plaque and stain; if it were, we wouldn’t have the need for adjunct cleaning methods. Often, the bulk of plaque and stain is removed with curettes, ultrasonic scalers and lavage, and the polishing paste is merely the finishing touch—the smoothing out that makes everything feel nice again after a major prophy jam session.

No, the reason that rubber cup polishing is the method used on probably 90% of patients in the United States is because it’s less technique-sensitive and equipment-sensitive. Not because it’s better. It’s also because of tradition. We find that prophy polishing is the standard of care because of what we experienced as patients in our childhood and also how we were taught to polish in school. You do it not because it’s right, but because it’s easier.

Rubber cup polishing is good enough … well, at least until it isn’t. Nowhere is the incompleteness of a prophy cup polish more evident than when trying to perform one on an orthodontic patient in full brackets and wires. Only then do you switch up your routine and reach for an adjunctive polishing system. Why? Because you’re relatively inexperienced using alternatives like air polishing on a regular basis, which translates into a messy melee for you and the patient, so the trade-off needs to seem “worth it.”

The only way to combat inexperience, though, is with experience, which you won’t get unless you start using your prophy jet on a regular basis. This means you’re being challenged to replace your prophy angle with the air polisher—yes, even on patients without a lot of stain or without orthodontia! But first, let’s dispel some of the biggest myths about air polishing that may have already caused you to dismiss the thought of making this change.

Myth #1: Air polishing is too messy.

It can be, but only during the learning phase or if you’re using poorer-quality equipment.

After air-polishing my patients almost exclusively for more than 10 years, I’ve found that the Dentsply Prophy Jet and Cavitron Jet Plus machines are unmatched for not only longevity and quality but also the ability to minimize overspray. Some lesser brands may not mix the water and powder into a slurry properly, so you end up with excessive powder all over the patient’s shoulders afterward. If you learn how to adjust the powder control, better angulation, correct working distances between the jet nozzle and the tooth, suction management and even patient positioning, over time you will realize that air polishing is no more of a cleanup disaster than prophy paste.

Myth #2: Patients hate the taste of baking soda.

What’s worse when you go to the beach on a windy day: tasting salt spray or biting into a sandy hot dog? I’d much rather taste the ocean. Why? Because it’s expected. You expect to taste salt water when you splash in the waves. The same can be true for your patients if you prepare them before you blast: Let them know exactly what to expect before you use the air polisher on their teeth for the first time. Explain why you’re using it instead of pumice, and you may be surprised at how many patients are agreeable about trying something new, especially if it benefits them. Try to use a powder that has flavoring as well, because this reduces patients’ perception that they’re being scrubbed down with household cleaning agents.

Myth #3: Air polishing doesn’t clean as well or feel as clean as prophy paste.

These should probably each be their own myths, but since they’re related we’ll keep them together. While prophy paste spins around in circles and does smooth the teeth nicely, guess what? Polishing paste also has a way of exaggerating the feeling that the mouth is dirty. Maybe your patient experiences this:

- Prepolish:“My teeth feel normal—a little grimy, but nothing I can’t handle.”

- Midpolish: “I have a mouth full of soul-crushing tiny rocks and sand that will kill me if I swallow.”

- Postpolish: “Wow, smooth teeth! What a relief that’s over. Much better than grit!”

It’s interesting how perception can be shaped by going to extremes. This same contrast is what makes people think that black charcoal toothpaste makes their teeth whiter. There’s not much of a “midpolish” grit with air polishing if you’re using sodium bicarbonate, however, because it has low abrasiveness—especially compared with pumice. Also, because it can be directed into pits, fissures and interproximal spaces, air polishing cleans at least 30% more of the tooth surfaces than rubber cup polishing. Be honest: How well do you polish the occlusals of molars with a prophy angle? You may be surprised at how often you’ve been neglecting certain areas of your patients’ teeth after you’ve switched to air polishing for a while.

Myth #4: Air polishing will make sensitive teeth more sensitive.

The opposite is more likely, actually. Every once in a while, I’ve encountered a patient whose roots were too sensitive for the air polisher, but the vast majority of patients with sensitive teeth do better than expected. This is likely because bicarbonate crystals are capable of blocking the openings of the dentinal tubules. Just be cautious not to hover over individual root surfaces for very long and you should be fine.

As an alternative to the Prophy Jet, there are air polishers that utilize glycine powder or erythritol. These newer powders are not only friendly to sensitive root surfaces, but they are also gentle enough to use for subgingival biofilm management.

Myth #5: The aerosol created by air polishing creates excessive contamination.

That’s why preprocedural rinsing is recommended as a universal precaution to reduce airborne bacteria—not just for air polishing, but also for ultrasonic scaling and even for prophy cup polishing. While it is true that jet polishing creates more aerosol than prophy angles, there’s not a significant difference in bacterial overspray caused by jet polishers versus ultrasonic scalers.

Myth # 6: Air polishing is more expensive.

Economics is certainly a consideration when it comes to implementing any technology. The initial setup cost for a quality jet polishing system, including an adequate number of inserts to maintain proper sterilization, can be daunting. However, once the equipment is in place, there’s much less waste compared to disposable prophy angles and single-serve prophy paste cups. The polishing powder is the only recurring expense once the system is in place, and you’ll find that the cost of it can be significantly less than polishing paste. My favorite sodium bicarbonate powder is supplied in simple tear packets by Young Dental and has excellent consistency and flavor, in addition to being affordable.

Probably the best reason to implement air polishing, however, is because in the long run it’s going to be less expensive for the practice in terms of efficiency. A patient with moderate staining takes less time to polish with an air polisher than a patient with light staining and a prophy cup. This means less operator fatigue, especially if you begin mixing up your routine and becoming flexible as to when you polish during a prophy. It doesn’t need to be at the end to be thorough, or even to gain patient acceptance.

The challenge

Even if you often still reach for the rubber cup at the end of an appointment, you will find that having strong air-polishing skills will help you better tailor the care you provide to meet each patient’s needs, instead of feeling like you’re running each mouth through the exact same routine, all day, every day. I didn’t even go into depth about the newer types of air-polishing systems available out there for you to try! But that’s because the first step you need to make is the step away from your prophy angle. Do it for a week, especially if you already have a neglected air polisher somewhere in your office. Dust it off, be patient, and rise to the challenge that you’ve made to yourself to change this one thing for a bit. You will be a better clinician for it.

Trish Walraven RDH, BS is a dental hygienist who lives in the suburbs of Dallas/Fort Worth. She was very reluctant to move all of her patients to jet polishing when her co-hygienist first suggested the change, but is very grateful to her and to all the patients over the years whose encouragement and feedback helped her realize that there was no going back to prophy cup polishes.

Ready to roll? Here’s a video tutorial from Dentsply to get you started:

A blogger since 1997, Trish Walraven, RDH, BSDH is a practicing dental hygienist in the suburbs of Dallas, Texas and marketing manager for

A blogger since 1997, Trish Walraven, RDH, BSDH is a practicing dental hygienist in the suburbs of Dallas, Texas and marketing manager for  Do you know how sometimes, when you get a new piece of equipment, it’s so Shifta La Paradigma that you can’t even THINK about working without it? You get a little anxious about the possibility of it failing and having to go back to the old way of doing things. What do you do?

Do you know how sometimes, when you get a new piece of equipment, it’s so Shifta La Paradigma that you can’t even THINK about working without it? You get a little anxious about the possibility of it failing and having to go back to the old way of doing things. What do you do? Opinion #2: Cords are better. And worse.

Opinion #2: Cords are better. And worse.

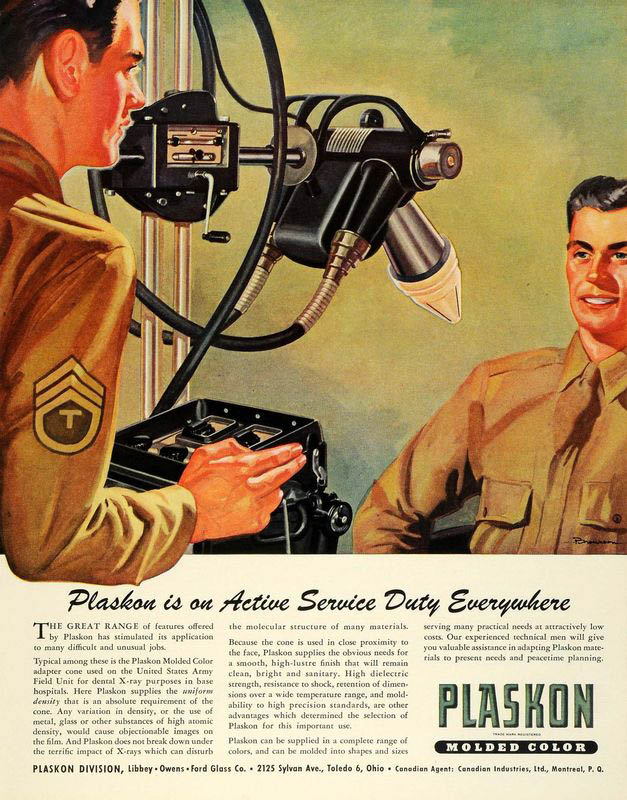

Admit it, you can’t help but call the long cylindrical chunk of metal pointing out from your x-ray machine anything but a cone. Even though it probably wasn’t a cone when you were in dental school. It hasn’t been a cone for over 30 years. But maybe you’re old enough to remember a cone getting pointed at you when you were a kid, like I am.

Admit it, you can’t help but call the long cylindrical chunk of metal pointing out from your x-ray machine anything but a cone. Even though it probably wasn’t a cone when you were in dental school. It hasn’t been a cone for over 30 years. But maybe you’re old enough to remember a cone getting pointed at you when you were a kid, like I am.